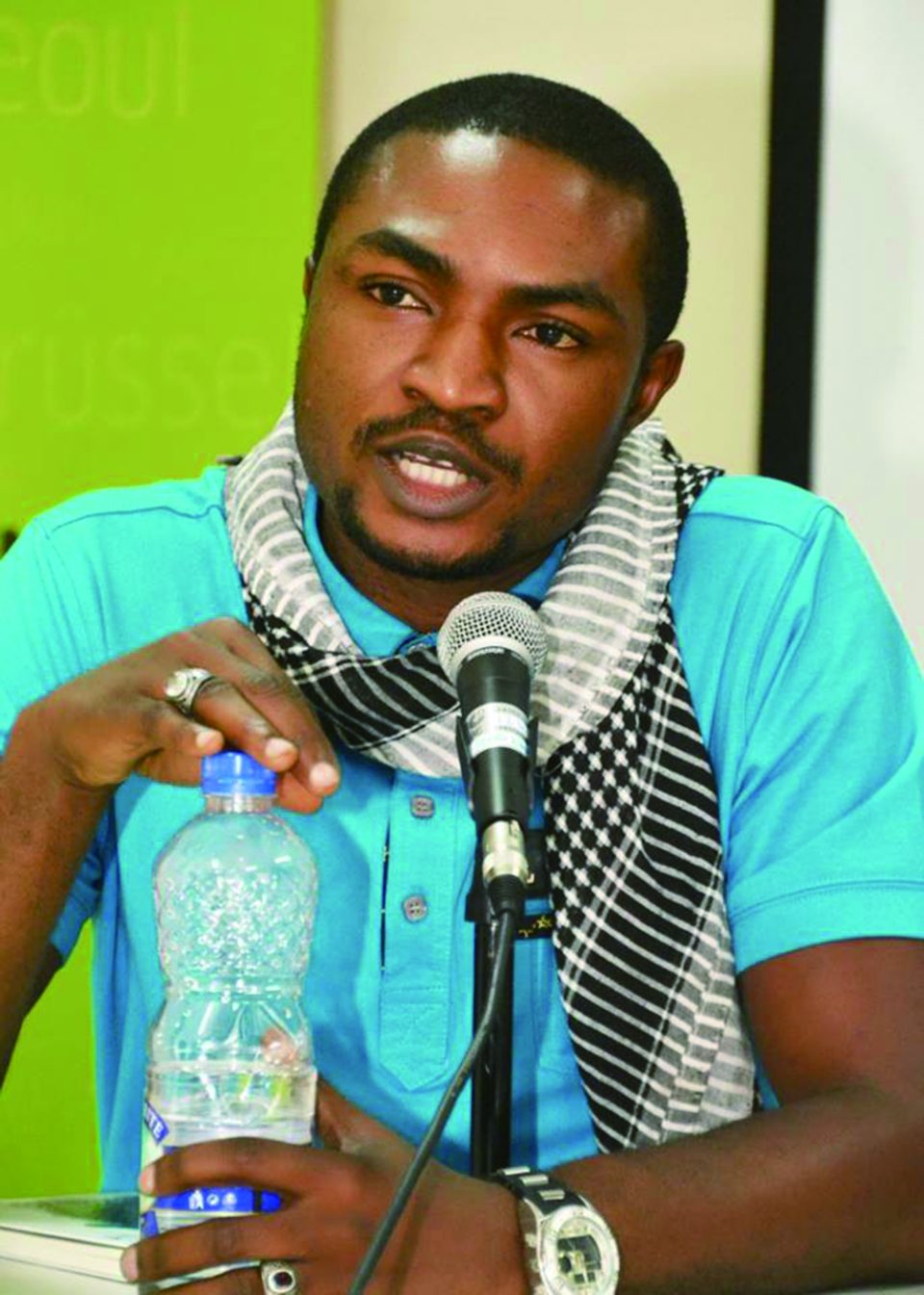

[특별인터뷰] 30년 연하와 사랑에 빠진 55세 여성 다룬 나이지리아 작가 아부바카르

나이지리아문학상 수상 ‘붉은 계절의 꽃’ 작가

작년 모국 이어 2016년 런던서도 출판 큰 인기

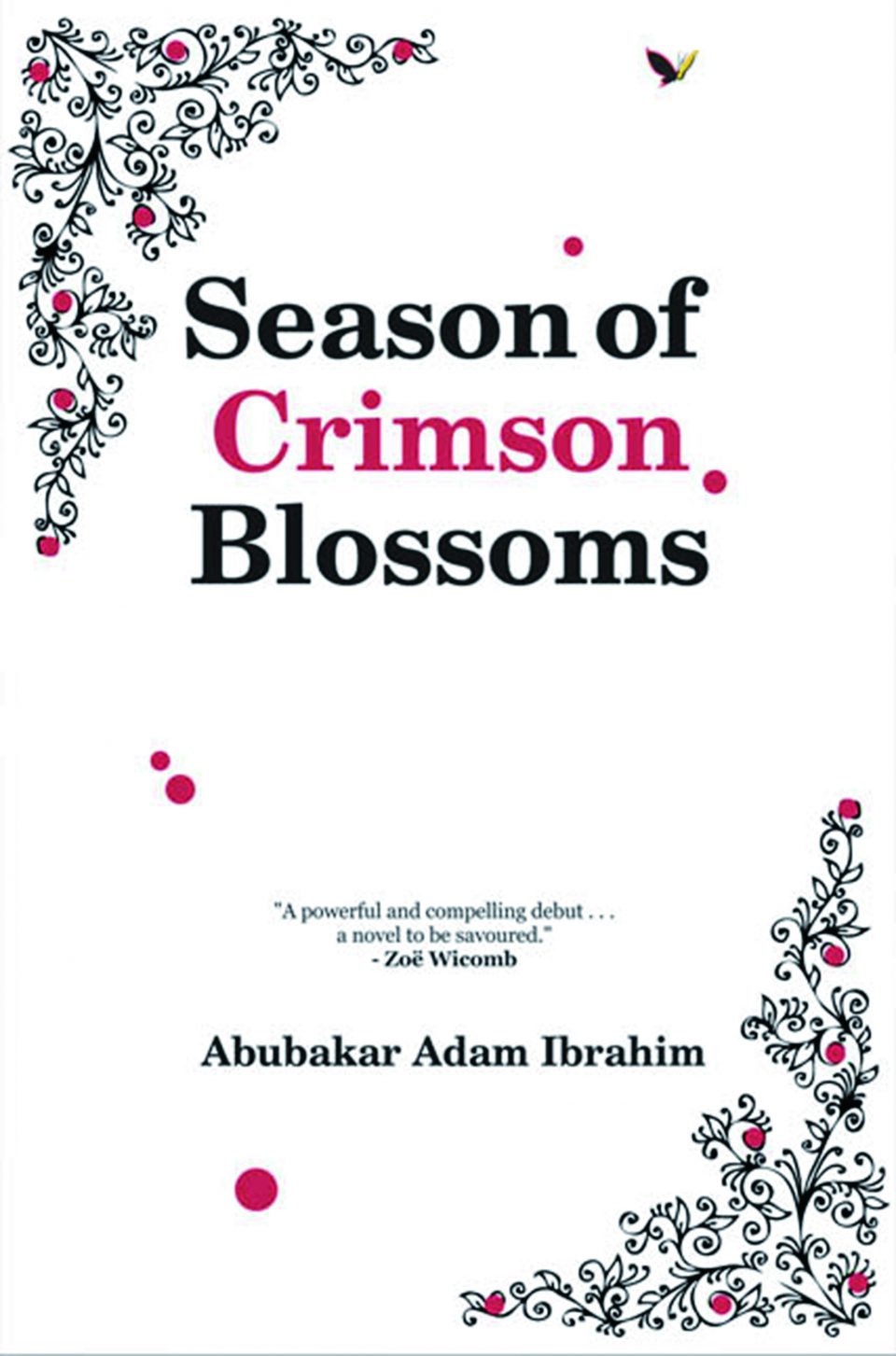

[아시아엔=아시라프 달리 <아시아엔> 아랍어판 편집장] 나이지리아문학상을 받은 <붉은 계절의 꽃>(Season of Crimson Blossoms)은 라고스에서 2015년, 런던에서 2016년 출판됐다. 작가 아부바카르 아담 이브라힘은 <아시아엔> 인터뷰에서 나이지리아의 전래동화 구전 풍습이 아프리카 작가들의 작품세계에 끼치는 영향에 대해서 자신의 경험과 문학 속에서 어떻게 녹아 있는지 등에 대해 설명했다.

아부바카르는 “500개가 넘는 언어가 통용되는 나이지리아에서 어느 한 부족에 치우치지 않고 최대한 많은 독자들에게 다가가기 위해 영어로 글을 쓴다”고 했다.

그는 “특정한 문화가 아니라 모든 인간이 공유하는 인간조건에 대한 글을 쓰고 있다”며 “<붉은 계절의 꽃>이 전통적인 이슬람 마을에서 30년 연하의 남자와 사랑에 빠지는 55세 여성의 이야기”라고 소개했다.

기자기도 한 아부바카르 아담 이브라힘은 “기자의 일이 작가의 그것보다 더 수고롭지만 사람들에게 훨씬 가까이 다가갈 수 있는 기회를 준다”며 “두 일 모두 소중하다”고 말했다. 그는 준비하고 있는 소설과 단편집도 있다고 아부바카르 아담 이브라힘은 귀띔했다.<번역 윤석희 기자

다음은 영문 원본.

The Season of AbubakarAdam Ibrahim Blossoms;

The New World Literary Voice from Nigeria

Interviewed by: Ashraf Aboul-Yazid (Dali)

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim is a Nigerian writer and journalist. He is the author of the novel Season of Crimson Blossoms (published by Cassava Republic Press, London in 2016 and Parresia Publishers, Lagos, 2015), which recent won the Nigeria Prize for Literature, one of the richest literary prizes in the world.

It follows on the success of his short story collection, The Whispering Trees published in 2012, which was shortlisted for the 2013 Caine Prize for African Writing, long-listed for the Etisalat Prize for Prose and is a recommended text in several Nigerian universities.Besides being awarded the 2013 Gabriel Garcia Marquez Fellowship in Colombia and the 2015 CivitellaRanieri Fellowship in Italy, Abubakar is listed in the Hay Festival Africa39 list of the most promising Sub-Saharan African writers under the age of 40. He also won the BBC African Performance Playwriting Competition in 2007. Abubakar has been announced as the winner of the Goethe Institute and Sylt Foundation African Writer’s Residency Award for 2016, which he will take up in Sylt, Germany, where he will spend a couple of months writing his new novel.

We firstly met in Seoul, but our connection is still alive following his world-wide success. I started my interview by asking him about the literary roots he grew with when he wanted to keep the passion of narration.

Well, I suppose that all writers encounter a certain kind of story-telling tradition at some point in their lives that helps them launch as writers, for some, it comes earlier than others. Storytelling was a natural instinct for me and it started with drawing pictures that told stories. We used to have a strong story-telling tradition with old women narrating stories to eager children by the fireside. I think mine was one of the last generations that enjoyed this kind traditional storytelling because, as children, we had a girl, who was older than us telling us stories in the evenings, sharing folklores and morality tales as old people used to do. By the time I was a teenager it was clear writing was my preferred choice of artistic expression and I have worked on building my craft ever since.

Do you think that when Wole Soyinka won the Noble prize in literature? He gave the Nigerian authors a world stand to launch their careers and works.

Every success by an author has resonance within the literary communities that identify with that author. When Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart became one the most read literary text by an African Writer, it inspired, and I imagine it still does, generations of writers. The same can be said with Soyinka’s Nobel Prize win and it was the same when Ben Okri won the Booker Prize. But for different generations, there are different inspirations and moments that are pivotal to the literary trajectory of a people.

How is it good or not to write in a country with multi-language people like Nigeria?

It has always been a preoccupation for certain writers what language they should write in and NgugiwaThiongo’s assertions on this are very well articulated and documented. It is not necessarily something I agree with even if I think it is a conversation we need to have, which in fact we have been having for the last four decades. For me, it was easy to choose to write in English. It is not a language that dictates to me, but one I see as a vehicle to convey my stories to the widest possible audience. For a country like Nigeria with anything between 500-700 languages, there has to be a common language that unifies all these ethnic nationalities and English happens to be convenient medium. I write human stories, stories that explore the human condition so I want people from all over the world to be able to access these stories.

Could you give us your behind scene story of publishing your work in London with African publishing house there?

Well, I have had my Nigerian publishers, Parresia, who published my debut, a collection of short stories in 2012. It was natural they would publish the Nigerian edition of my novel. Finding an international publisher though was challenging. I was told that the writing was beautiful but the story was not “for a certain market.” As absurd as that was, it was, of course, understandable because I did not feel the need to water down my story to satisfy the taste of certain markets. It was a story that I felt needed to be told the way it was told to capture the complexities of . Fortunately, Cassava Republic, a Nigerian publishing house was at that point setting up business in London with the aim of taking African stories to the world and they took interest in the manuscript. They were so passionate about it that it was natural to publish with them and I am happy I did. We are having an exciting ride.

How do you introduce your most recent novel Season of Crimson Blossoms in few sentences to African and Asian readers?

Season of Crimson Blossoms is the story of BintaZubairu, a devout Muslim woman, mother and grandmother, who at 55 starts an explicit relationship with a criminal named Hassan Reza, who is 30 years younger than her. Set in a conservative Muslim community, the relationship between the two lovers did not go down well with the community and with Binta’s children, who are all older than her lover.

You won the 2016 NLNG Nigeria prize for literature on the 12th of October 2016! It is one of the largest prizes for the literature in Africa and one of the richest ones in the world. I congratulate you on this unique achievement, but I would like readers to know more about the prize, with mentioning on the literary scene in Nigeria.

As you mentioned it is one of the richest literary prizes in the world. It is awarded every year and rotates among the genres of prose, poetry, drama and children literature so the next prize for prose will be awarded in the next four years. This is the 12th year of the prize and this year is the third time the prose prize is being awarded.

Considering your work in the field of journalism, how much positive and negative being a writer and a journalist at the same time.

The only negative I guess is that journalism takes more time from my creative writing but otherwise, the two have complemented each other for me. I have always been a writer and journalism was something I wanted to do to access people. The two have been complimentary for me.

Speaking of your future projects…

I am working on a couple of projects. I have a novel I am working on and there might be a collection of short stories but it is still early days for the novel so we will see how that goes.