라틴 아메리카의 지지 않는 태양 시몬 볼리바르

*아시아엔 해외필진 기고문을 한글번역본과 원문을 함께 게재합니다.

[아시아엔=아시라프 달리 아시아기자협회 회장] 시몬 볼리바르는 라틴 아메리카 역사에 있어서 단순히 역사적 인물이 아닌 지지 않는 태양과도 같은 존재다. 그의 이름을 따서 국명을 지은 볼리비아부터 그의 이름이 들어간 지명이 20곳이나 있는 콜롬비아까지 볼리바르란 이름은 라틴아메리카 곳곳에서 찾아볼 수 있다.

볼리바르가 태어나고 또 활동했던 베네수엘라는 더욱 그렇다. 베네수엘라의 공식 명칭은 ‘볼리바르 베네수엘라 공화국’이다. 수도 카르카스에는 그를 기리는 동상들과 무수히 많은 벽화들이 자리해 있다. 공항의 이름 역시 위대한 ‘해방자’의 이름에서 유래됐다. 볼리바르를 수식하는 ‘해방자’란 단어는 그가 라틴 아메리카와 전세계에 얼마나 큰 공헌을 했는지 알 수 있게 하는 대목이다.

필자의 모국 이집트의 수도인 카이로의 가장 아름다운 광장의 이름 또한 볼리바르에서 유래됐다. 1979년 2월 개장된 이 광장에는 2.3미터 높이의 웅장한 청동 동상이 우뚝 서 있다. 베네수엘라에서 온 두 예술가 마누엘 블랑코와 카르멜로 타보코가 제작한 동상은 이집트와 볼리바르 사이의 강한 유대감을 상징한다.

이집트와 베네수엘라는 역사적으로 위대한 해방지도자를 갖고 있다는 공통점이 있다. 20세기 중반 이집트 가말 압델 나세르 대통령의 집권기 동안 이집트와 남미 국가들은 혁명의 공감대가 형성됐는데, 이에 대한 경의와 존경을 표하기 위해 베네수엘라 수도 카라카스에는 나세르의 동상이, 이집트 수도 카이로에는 볼리바르의 동상이 세워졌다.

시몬 볼리바르는 1783년 7월 24일 현재의 베네수엘라 수도 카라카스에서 태어나 1830년 12월 17일 콜롬비아 산타 마르타 부근에서 사망했다. 그는 라틴아메리카가 스페인의 식민지배를 받던 시절 그라나다 주(콜롬비아, 에콰도르, 파나마, 베네수엘라 일대)에서 반란군을 이끌었으며, 그란 콜롬비아와 페루, 볼리비아의 대통령을 지낸 정치가이기도 하다.

스페인 혈통의 베네수엘라 귀족의 아들로 태어난 볼리바르는 3살과 9살 때 각각 아버지와 어머니를 여의면서 후견인이 된 외삼촌의 가정에서 자랐다. 볼리바르의 스승 중 한 명인 시몬 로드리게스는 자유주의 철학자 장 자크 루소 밑에서 수학했었는데, 그 영향으로 볼리바르는 자유주의 사상에 눈을 뜨게 됐다.

볼리바르는 16세 때 유럽으로 유학을 떠났고, 스페인에서 3년간 머물다 귀족의 딸과 혼인해 카라카스로 돌아왔다. 그러나 결혼한 지 1년도 채 되지 않아 신부가 전염병으로 사망했는데 이는 볼리바르가 젊은 시절부터 정치 경력을 쌓게 된 계기가 됐다.

나폴레옹이 전성기를 구가하던 1804년 볼리바르는 다시금 유럽으로 떠났다. 그는 파리에서 멘토인 로드리게스의 도움을 받아 볼테르, 몽테스키외, 루소, 존 로크, 토마스 홉스 등 유럽 합리주의 사상가들의 저서를 탐독했다. 그 중 루소와 몽테스키외는 볼리바르의 정치관에, 볼테르는 볼리바르의 인생관 형성에 큰 영향을 미쳤다.

볼리바르는 파리에 체류하는 동안 라틴아메리카 여정을 마치고 돌아온 독일의 학자 알렉산더 폰 훔볼트와도 교류했는데, 훔볼트는 볼리바르에 “라틴 아메리카는 스페인으로부터 독립할 준비가 돼 있다”는 말을 건넸다. 이에 깊은 감명을 받은 볼리바르는 로마의 몬테 사크로 언덕 위에 올라 ‘라틴 아메리카를 해방시키겠노라’고 다짐했다.

볼리바르는 1807년 베네수엘라로 돌아와 동부의 도시들을 답사했다. 그로부터 1년 후 나폴레옹의 침공으로 스페인의 지배력이 약해졌을 즈음 라틴아메리카 독립운동이 본격적으로 전개됐다. 나폴레옹 역시 스페인 식민지들의 지지를 얻는데 실패했고, 식민지들도 관례에 따라 그들의 관리자를 스스로 지명할 권리가 있다고 주장했다.

1810년 4월 19일 스페인 총독부는 베네수엘라에서 추방됨에 따라 군사의회가 권력을 장악했다. 그해 7월 볼리바르는 식민지배 독립을 인정받고 군수물자 등의 지원을 얻고자 영국으로 떠났다. 비록 공식협상엔 실패했지만 부수적인 이익을 얻었다. 볼리바르는 영국에 머물며 선진제도를 연구해 정치 커리어의 자양분으로 삼았다. 또한 베네수엘라 해방운동에 나섰다가 실패 후 망명해 있던 프란시스코 데 미란다를 설득해 함께 귀국하며 혁명의 대의를 확산시켰다.

1811년 3월 베네수엘라는 국민의회 주도로 헌법 초안을 만들기 시작했다. 볼리바르는 그들의 대표는 아니었지만 국가의 중대사가 달린 논쟁에 기꺼이 뛰어들었고, 그의 첫번째 공식 연설에서 “두려움 없이 국가 자유의 초석을 다지자. 망설임은 파멸이다”라고 외쳤다. 1811년 7월 5일, 베네수엘라는 오랜 투쟁 끝에 마침내 독립을 선언했다.

필자가 문인축제에 참석하기 위해 베네수엘라에 방문했을 당시 카라보보 전투를 기념하는 축제가 한창이었다. 카라보보 전투는 베네수엘라의 독립을 확고히 한 전투로, 베네수엘라인들에게 매우 의미 깊은 역사적 사건이다.

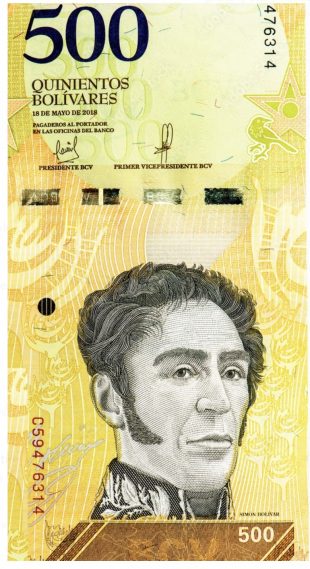

거리 곳곳에서 볼리바르의 기념품이 눈에 띄었다. 볼리바르를 연기한 배우들과 반갑게 인사도 나눴다. 가장 기억에 남는 것은 볼리바르의 모습이 담긴 화폐로, 상인과 물물교환을 통해 손에 넣었다. 말년의 볼리바르는 ‘왕’이나 ‘황제’ 같은 칭호보다는 ‘해방자’라는 칭호가 훨씬 더 마음에 든다고 말하곤 했다. 해방된 땅의 상징을 작은 주머니에 고이 간직한 채 베네수엘라에 작별을 고했다.

The Sun Never Sets on Simon Bolivar!

by Ashraf Aboul- Yazid, AJA President

240 years after his birth, Simon Bolivar is no longer just the name of a prominent historical figure, but has become a landmark whose name you can read from which the sun never sets; wherever you are on his continent: In Argentina, or in Bolivia that was named after his name, or Chile in one of the metro stations, or Colombia, which distributed his name to twenty parts of its lands; such as the name of one of its nine states of origin, or cities and neighborhoods, or parks and squares, or a bus station, or a mountain peak, or even a TV series, or the name of a cigar in Cuba, or a park in Costa Rica, or a province and port in Ecuador, or a metropolis in El Salvador, and a province in Peru , and a village in Uruguay.

As for Venezuela, it is the filling of the eye and the heart together, as it is in the official name of the country; the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, which is the name of a state, the name of its capital, and the name of a bridge on the border with Colombia. In addition to three statues in Caracas, the capital, there is his portrait on countless murals, even the theater on which we read poetry this month has the name of Simon Bolivar. The dam that is located on the Caroni River is named Bolivar. The airport in which we were received and from which we saw off our friends has the name of the great liberator. Rather, the title (the Liberator) refers to him, and is evidence of his role in the history of South America and the world.

Away from this continent, and similar to Australia, Belgium and the United States, I come from a country that puts Simon Bolivar name in one of its most beautiful squares in the Garden City neighborhood, in the middle of which is its statue, Simon Bolivar Square, in the distance between Tahrir Square and the Nile Corniche, in Cairo. It was opened on February 11, 1979, topped by the majestic statue weighing half a ton of bronze, with a length of 2.3 meters, and it is the statue that was sculpted by the Venezuelan sculptor Carmelo Tabaco, and its base was formulated by the artist Manuel Blanco, to come from Venezuela, and he stands as a witness to Egypt’s strong relationship with his mother country.

Nasser and Simon Bolivar: Face to Face

No one is surprised by the rapprochement between the two countries, as they were associated with two leaders of liberation, as the era of the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser witnessed a rapprochement of revolutionary ideas between Egypt and South American countries, and just as it witnessed a statue of Abdel Nasser in Caracas, this statue was placed in faith and in honor of the ideas of Simon Bolivar, one of the icons of the revolution that It rose against Spanish colonialism in South America, to liberate Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia.

Before traveling, when I visited the Venezuelan embassy in Cairo to get my visa stamped, His Excellency the Ambassador Wilmer Barrientos received me and led me to two panels at the entrance of the embassy, in Maadi, to see Nasser face to face with Simon Bolivar.

Sim?n Bol?var, liberator or libertador in Spanish, (born July 24, 1783, Caracas, Venezuela, New Granada [now in Venezuela] – died December 17, 1830, near Santa Marta, Colombia), was a Venezuelan soldier and statesman who led revolts against the Spanish government in the state of New Granada. He was president of Gran Colombia (1819-1830) and Peru (1823-1826).

The First School of Bolivar

Born the son of a Venezuelan aristocrat of Spanish descent, Bol?var inherited wealth and prestige after his father died when the boy was three years old, and his mother died six years later, so that his uncle managed his inheritance and provided him with guardians. One of his teachers was Simon Rodriguez, who had a deep and lasting influence on him. Rodriguez, a student of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, led Bolivar into the world of liberal thought in the eighteenth century.

On our tour, we arrived at that first school, which was a house where Simon Rodriguez was embraced and gave him educational classes. We saw classes that taught drawing, dancing, and music, as well as boxes that still held bottles from that first house, chairs, and drawings.

At the age of sixteen, Bol?var was sent to Europe to complete his education. He lived in Spain for three years, and in 1801 married the daughter of a Spanish nobleman, with whom he returned to Caracas. The young bride died of yellow fever less than a year into their marriage. Bol?var believed that her tragic death was the reason he took up a political career while still a young man.

In 1804, when Napoleon was nearing the pinnacle of his career, Bolivar returned to Europe. In Paris, under the renewed guidance of his friend and mentor Rodriguez, he immersed himself in the writings of European rationalist thinkers such as John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, Georges Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Jean le Rond d’Alembert, and Claude D’Alembert. – Adrien Helv?tius, as well as Voltaire, Montesquieu and Rousseau.

The latter two had the most profound influence on his political life, but Voltaire shaped his philosophy of life. In Paris he met the German scholar Alexander von Humboldt, who had just returned from his trip through Latin America and told Bol?var that he believed the Spanish colonies were ready for independence. This idea took root in Bolivar’s imagination, and on a trip to Rome with Rodriguez, where they stood on the heights of Monte Sacro, he vowed to liberate his country.

Liberator, not a king or emperor

In his later days, he always insisted that the title of “liberator” was superior to any other, and that he would not exchange it for the title of king or emperor. In 1807 he returned to Venezuela by way of the United States, and visited the eastern cities. The Latin American independence movement took off a year after Bolivar’s return, as Napoleon’s invasion of Spain destabilized Spanish power. Napoleon also failed completely in his attempt to gain the support of the Spanish colonies, which claimed the right to nominate their own officials following the example of the mother country.

On April 19, 1810, the Spanish governor was formally deprived of his powers and expelled from Venezuela. The military council took over. For help, Bolivar was sent on a mission to London, where he arrived in July. His task was to explain to England the plight of the revolutionary colony, to recognize it, and to obtain arms and support. Although he failed in his formal negotiations, his stay in the English language was fruitful in other respects. It gave him the opportunity to study the institutions of the United Kingdom, which remained for him models of political wisdom and stability. More importantly, he furthered the cause of revolution by persuading the Venezuelan exile Francisco de Miranda, who in 1806 had single-handedly attempted to liberate his country, to return to Caracas and take over the leadership of the independence movement.

In March 1811, the National Convention met in Caracas to draft a constitution. Bol?var, though not a delegate, threw himself into the debate that agitated the country. In the first public address of his career, he declared, “Let us lay the foundation stone of national liberty without fear. Hesitation is doom.” After long deliberations, the National Assembly proclaimed the independence of Venezuela on July 5, 1811. We were in the midst of celebrations marking the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Carabobo that led to Venezuela’s independence, a battle of great historical and cultural importance to the Venezuelan people, as it secured the country’s independence and the end of Spanish domination.

My Bolivar, in Heart and Pocket!

I was in Venezuela, number 200 in the color of the flag roaming the country, and we were participating in the 17th edition of its Mundial Poetry Festival, and the 1st World Congress conference of the World Poetry Movement (WPM), which we began in Medellin, Colombia, after we participated in the 33rd Edition of Medellin International Poetry Festival.

I searched for a Bolivarian souvenir. It is true that there is a picture of me reading poetry at Bolivar’s theatre, and my picture in front of his statue, and near one of his murals. I also have photos of his tomb! I even met more than one actor who embodied Bolivar on cultural occasions, and in the museum I shook hands with him, but I was fascinated by his picture on the Bolivarian currency, so I stipulated a seller The electric charger of my phone to give me the rest of the dollars in Bolivarian banknotes, and a Venezuelan poet of Lebanese origin gave me another note, and so I bid farewell to the land of the liberated, while I carried it in my pocket, to join the memorabilia of exceptional personalities.