[특별기고] 트럼프-김정은 과연 성공할 수 있을까?

[아시아엔=레온 시걸 동북아 미 사회과학연구소 안보협력프로젝트 총괄, <Disarming Strangers: Nuclear Diplomacy with North Korea> 저자] 미국 트럼프 대통령과 북한의 김정은 위원장의 북미정상회담은 한반도가 핵무기로부터 어느 정도 자유로워졌을 뿐 아니라 동북아 군사전략에 대한 변화의 가능성을 보여주었다. 두 정상은 “새로운 미국-조선민주주의인민공화국 관계의 구축”과 “한반도에 대한 지속적이고 안정적인 평화체제 성립”에 대해서 약속했다. 아직 협의되지 않은 세부적인 내용들에 대해서는 “가장 빠른 시일 내에” 시행될 다음 협상들과 워싱턴이나 평양에서 열릴 두 번째 정상회담에서 확실히 규정하기로 하였다.

정상회담이 마무리된 지금 양국 정상에겐 어떤 과제가 남겨져 있나? 우선 두 정상은 세부적인 단계에 대해서 실질적인 논의를 이어가야만 한다. 첫째는 북한의 핵물질 생산을 막고, 중거리 미사일과 대륙간 탄도탄 배치 역시 중단돼야 한다. 이같은 확실한 조치가 지연될수록 북한은 플로토늄 및 우라늄 생산을 확대하고 미사일 배치를 늘리려는 게 아니냐는 의심을 받게 된다.

북한의 가시적인 조치가 이춰질 경우 워싱턴은 북핵문제 발생 이전에 제정된 적성국교역법에 따른 에너지 원조를 재개하고 한반도의 종전선언을 이끌어 낼 수 있을 것이다. 북미정상회담의 결과들에 관한 검증은 2008년 10월에 북한이 6자회담 당사국의 전문가들과 IAEA에 대해 요청했던 북핵 관련 정보의 전면적인 공개 수준으로 이뤄질 전망이다.

이 전면적인 정보 공개에는 ‘개인 서류·비망록’ ‘기술자 인터뷰’ ‘핵 물질 및 장비에 대한 의학적 측량’ 등과 재처리 공장·핵연료 공장의 ‘환경 샘플과 핵폐기물 샘플’ 등이 포함되어 있다. 이것들만으로도 북한이 플로토늄을 얼마나 생산했는지 알아낼 수 있기 때문이다. 북한은 상호협약에 따라 미신고 지역에 접근하는 것도 허용키로 동의했다.

이같은 변화는 그동안의 적대감을 종식시키고 한반도에 평화 체제를 가져오기 위한 미국의 북한 승인, 에너지 원조 제공 등의 발판이 될 것이다. 워싱턴과 서울의 정치·경제 정상화, 한국전쟁의 종전 선언, 북미수교 그리고 지역안보 동맹의 선제적 해결 없이는 북핵 및 미사일 프로그램을 중지시키라고 설득하기엔 쉽지 않다.

김정은 위원장이 남북회담 및 북미회담에서 약속한 것들을 지킬 의향이 있는지 여부는 이것들에 대한 완전한 이행으로 확인될 것이다. 물론 그 기간은 몇 년이 걸릴 수도 있다. 그때 비로소 김정은 위원장의 약속에 대한 실천의지를 최종 확인 할 수 있을 것이다. <요약번역 조일영 인턴기자>

아래는 <글로벌 아시아>에 게재된 기고문 전문입니다.?

Can Trump and Kim Work It Out Despite Past Failures?

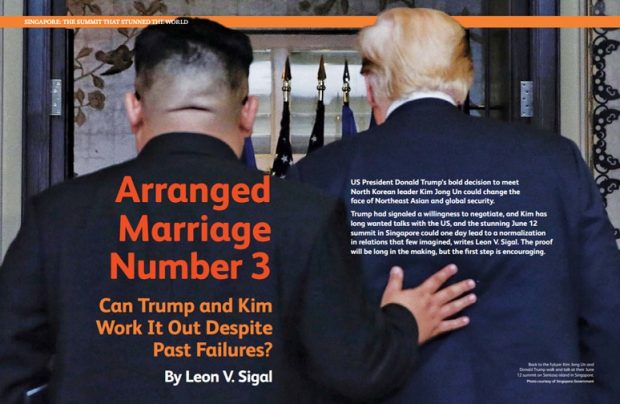

It was a riveting moment. Two enemies talking for a change. The Singapore summit between US President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim Jong Un of North Korea raised the prospect not only of a Korean Peninsula free of nuclear weapons but also of a strategic realignment in Northeast Asia. In Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s words, it could lead to “a fundamentally different strategic relationship between our two countries.”

Unlike previous US-North Korea agreements, the leaders themselves signed a joint statement this time committing Pyongyang to “complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula,” without spelling out specifics. They pledged to “establish new US-DPRK relations” and “build a lasting and stable peace regime on the Korean Peninsula.” The details that have not yet been agreed will be ironed out at follow-on negotiations to commence at the “earliest possible moment” and at a second summit meeting in Washington or Pyongyang.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in deserves praise for bringing Trump and Kim together to exchange vows. Onlookers wondered whether hope would triumph over experience in this arranged marriage, the third try for North Korean rapprochement with the US.

To understand why this third marriage may last where others have failed, it is essential to understand what the North Korean leader was up to. Contrary to speculation about the end of the alliance with South Korea, the abandonment of the nuclear umbrella, the withdrawal of US forces, a Marshall plan, or even written security assurances, what Kim really wants is an end to US enmity.

From Pyongyang’s vantage point, that aim was the basis of the 1994 Agreed Framework that committed Washington to “move toward full normalization of political and economic relations,” or, in plain English, to end enmity. It was also the essence of the September 2005 Six-Party Joint Statement, which bound Washington and Pyongyang to “respect each other’s sovereignty, exist peacefully together, and take steps to normalize their relations subject to their respective bilateral policies,” as well as to “negotiate a permanent peace regime on the Korean Peninsula.”

For Washington, the point of these agreements was the abandonment of Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile programs. Both agreements collapsed, however, when Washington did little to implement its commitment to reconcile and Pyongyang reneged on denuclearization.

What better way for Trump to indicate a readiness to reconcile than to sit down with Kim and say, as Trump has, that he is prepared to negotiate an end to the Korean War and to normalize relations ? something his predecessors never did ? as well as to suspend joint major military exercises with South Korea?

Nor was Trump’s willing engagement as impulsive as critics would have it. During the 2016 campaign, candidate Trump repeatedly talked about negotiating with North Korea, a signal not missed in Pyongyang. Within days of his inauguration, Trump signed off on delivery of a token amount of flood relief, the first humanitarian aid to North Korea in five years.

In February 2017, he authorized an invitation for Choe Son Hui, director-general of the American division in the North Korea Foreign Ministry, to meet in New York with Joseph Yun, the US ambassador in charge of negotiating with North Korea ? only to cancel the meeting over the assassination of Kim’s half-brother in Kuala Lumpur. Yet within weeks, Yun began talks via the “New York channel” and later met Choe in Oslo and Pyongyang. That fall, Yun was authorized to drop preconditions for negotiations. Intelligence channels were also activated.

Kim has also long signaled his interest in negotiating. Even his byungjin strategic line, promulgated on May 31, 2013, had a key condition implying that it could stop testing nuclear weapons and missiles and generating fissile material. It spoke of “carrying out economic construction and building nuclear armed forces simultaneously under the prevailing situation,” or, as North Korean diplomats explained it, as long as the “hostile policy” persists.

In its decision of May 8, 2016, the Seventh Korean Workers’ Party Congress characterized byungjin as “simultaneously pushing forward economic construction and the building of a nuclear force and boosting a self-defensive nuclear force both in quality and quantity as long as the imperialists persist in their nuclear threat and arbitrary practices.” The conditionality of byungjin implies that North Korea might eventually limit its missile and nuclear weapons production.

Kim kept hinting at a stopping point for tests. In “guiding” the launch of the Hwasong-12 intermediate-range missile on Sept. 16, 2017, Kim said: “We should clearly show the great-power chauvinists how our state attained the goal of completing its nuclear force despite their limitless sanctions and blockade,” underlining the need to finalize the work with “the mobilization of all state efforts as it nearly reached the terminal.” That statement raised the possibility of suspending tests once the terminal was reached.

A day after Kim’s New Year’s Day speech one year earlier, President-elect Donald Trump tweeted, “North Korea just stated that it is in the final stages of developing a nuclear weapon capable of reaching parts of the United States,” adding, “It won‘t happen.” By stopping nuclear and missile testing just short of having a proven thermonuclear weapon and an ICBM with a re-entry vehicle capable of delivering it to all of the US, Kim Jong Un has made it possible for Trump to get his wish.

Now that the summit is over, the parties have to follow up by negotiating detailed steps. The first order of business is to induce North Korea to suspend production of fissile material and possibly suspend deployment of intermediate- and intercontinental-range missiles. Remote monitoring may prove of some use, but delaying suspension to negotiate detailed verification would allow time for more plutonium and highly enriched uranium to be produced and more missiles to be fielded in the interim.

Verification could be pursued along the lines of a joint document from October 2008, in which North Korea agreed to allow “full access” to “experts of the six parties” with the IAEA “to provide consultancy and assistance” for “safeguards appropriate to non-nuclear-weapons states.” It included records, “personal notebooks” and “interviews with technical personnel,” “forensic measurements of nuclear materials and equipment” and “environmental samples and samples of nuclear waste” at the three declared sites at Yongbyon ? the reactor, the reprocessing plant and the fuel fabrication plant. This might suffice to ascertain how much plutonium North Korea had produced, and, if not, Pyongyang also agreed to allow “access, based on mutual consent, to undeclared sites.” This will require further steps to end enmity, including a commitment by Washington to begin a peace process in Korea, take steps toward diplomatic recognition, provide energy aid and allow reciprocal inspections in South Korea.

The chances of persuading North Korea to go beyond another temporary suspension to dismantle its nuclear and missile programs are slim without movement by Washington and Seoul toward political and economic normalization, peace talks for a formal treaty to end the Korean War, and regional security arrangements, among them a nuclear weapon-free zone that would provide a multilateral legal framework for denuclearization.

Whether Kim is willing to keep his pledge to disarm is mere speculation. Sustained diplomatic give-and-take followed by full implementation of commitments is the only way to find out. Dismantling production facilities and disarming will take years. So will convincing steps toward reconciliation. Only then will Kim reveal his willingness to give up his weapons.