싱가포르 정부 수립 뒷 얘기‥리콴유와 마하데바의 잘못된 만남

*아시아엔 해외통신원 기고문의 한글번역본과 원문을 함께 게재합니다.

[아시아엔=아이반 림 아시아기자협회 명예회장, 싱가포르 스트레이츠 타임스 선임기자 역임] 1957년 9월 27일, 싱가포르의 사회운동가 아루나살람 마하데바(당시 26세)가 영국에서 변호사로 활동하다 귀국 후 유력 총리후보로 떠오르던 리콴유(당시 34세)와 회동했다. 리콴유는 그의 법률사무소에서 마하데바에게 인민행동당(People’s Action Party)의 사무총장직을 제의했다. 리콴유는 마하데바가 노조의 특권을 내세우던 좌익과 맞서 싸우길 바랐다. 그는 또한 마하데바가 1959년에 열릴 싱가포르 총선에 출마하기를 원했다. 그러나 여기엔 전제조건이 있었다. 리콴유는 자신의 정치적 동료이자 사회주의운동을 이끌던 림 친 시옹과 결별하더라도 마하데바가 자신의 편에 설 것인지 알고 싶었다.

*역주: 당시 싱가포르는 영국 식민지로부터 자치를 인정받았지만, 완전 독립이 이루어진 1965년까지는 정치적 혼돈을 겪었다. 인민행동당은 탈식민지주의와 진정한 독립이라는 대전제 하에 사회주의에 가까운 노선으로 뭉쳤지만, 자본가와 노동자 사이의 이해관계가 더욱 복잡해지며 분열됐다. 이후 리콴유의 인민행동당은 중도우익, 림 친 시옹의 사회주의전선(Barisan Sosialis)은 좌익의 노선을 걷게 됐다. 사회주의전선은 1988년 싱가포르 최대 야당인 노동당에 흡수돼 역사 속으로 사라졌다.

하지만 사회주의 세력이 처한 상황을 잘 알고 있던 마하데바는 리콴유의 제의를 거절하며 “내 거취는 쟁점의 당사자들이 어떻게 해결하느냐에 달려 있다”고 말했다. 리콴유는 그럼에도 마하데바를 포섭하려고 노력했지만 돌아오는 것은 거절 뿐이었고, 이들은 서로 다른 길을 걷게 된다. 그리고 얼마 지나지 않아 리콴유와 인민행동당이 기자와 노조원으로 활동했던 마하데바를 적으로 분류한다는 자료가 공개됐다.

1957년 말라야 대학(University of Malaya)을 졸업한 마하데바는 ‘싱가포르 타이거 스탠다드’(Singapore Tiger Standard)라는 영자신문사에 취직, 급격한 소용돌이를 겪었던 싱가포르 정계를 취재했다. 이후 싱가포르 유력지 ‘스트레이츠 타임스’(The Straits Times)의 기자로 활동하면서 이따금씩 리콴유 총리와 언쟁을 벌이곤 했다. 리콴유는 그런 마하데바를 림 친 시옹의 좌익세력에 동조하는 당파 언론인으로 바라봤다.

마하데바는 1959년 부킷 티마(Bukit Timah)에서 선거 유세장에서 리콴유와 치열한 신경전을 벌인 적도 있다. 현장에서 마하데바와 눈이 마주친 리콴유는 “이번에는 어떤 기사를 쓰고 계신가? 우리 당이 총선에서 패배하도록 도와준 대가로 CIA한테서 돈을 받은 사람의 신상도 공개하지 않고 말이야!”라고 외쳤다. 싱가포르 정치인 츄 스위 키(Chew Swee Kee)를 염두에 두고 한 말이었지만, 그 당시만 해도 츄 스위 키가 공작활동에 가담했다는 사실이 공론화되진 않았다. 이에 마하데바는 “기자로서의 직업을 다할 뿐이며, 직접 조사하면서 얻은 정보만 기사로 쓴다”고 답했다.

만약 리콴유 총리가 특정인을 언급했다면, 마하데바도 프로답게 이와 관련된 기사를 썼을 것이다. 하지만 리콴유는 그런 내용이 공개된다면 정치적으로 역풍을 맞을 지 모른다는 판단 하에 참았다. 기자로서 사명감을 갖고 있었던 마하데바도 사회주의 노선에 동정심을 갖고 있었지만, 인민행동당에 도움이 될 지 모른다는 이유로 기사 작성을 포기하진 않았을 것이다.

민주사회주의 이념 접하며 폭 넓게 교류했던 마하데바

마하데바는 대학생 시절 사회주의자 동아리에 가입해 민주사회주의 이념을 접했다. 2차대전 이후 싱가포르에선 민주사회주의를 지지하던 엘리트 계층이 민족주의를 고취시키고 있었고, 마하데바도 영국으로부터의 독립운동에 동참했다. 당시 마하데바가 교류했던 운동가들은 훗날 식민지 반대운동을 주장하는 노조를 결성하기도 했다.

마하데바는 사회주의 잡지 ‘파자르’(Fajar)의 유통책임자 역할을 맡았으며, 좌익단체였던 ‘싱가포르 항만 이사진 협회’의 회장 자밋 싱(Jamit Singh)과도 가깝게 지냈다. 자밋 싱은 1955년 지역구 탄종 파가에서 승리하며 정치인생을 시작한 리콴유의 초창기 지지자 중 하나였다. 마하데바는 대학 졸업 논문으로 아시아 항만 노동자들의 급여 구조에 대해 연구했고, 이를 눈 여겨 본 리콴유가 그에게 인민행동당의 중직을 제안했던 것이다.

다양한 이들과 교류하던 마하데바는 화교와 민간을 주축으로 반식민지 운동을 이끌었던 노조위원장 림 친 시옹(Lim Chin Siong)과도 친분을 쌓았다. 림 친 시옹은 싱가포르 초대 총리로 거론될 정도의 인물이었다. 이와 비슷한 시기, 영국 유학파 출신의 변호사 리콴유는 경제학자 고 켕 스위(Goh Keng Swee), 과학자 토흐친차이(Toh Chin Chye) 등과 런던에서 탈식민지 운동을 전개하기 시작했다.

의기투합한 리콴유와 림 친 시옹은 인민행동당을 창당, 싱가포르 자치정부 수반을 선출하는 선거에 도전장을 내밀었다. 당시 선거운동에 참여했던 마하데바는 1959년 3월 인민행동당이 선거에 승리하고, 리콴유가 싱가포르 자치 정부의 초대 총리로 권력을 잡는 광경을 목격했다.

싱가포르 정치사의 운명을 갈랐던 말라야 연방

그러나 두 거목의 동행은 그리 길지 못했다. 1961년, 싱가포르가 동남아의 이권을 지키기 위해 영국 왕실령인 말라야 연방(Federation of Malaysia)에 가입에 대해 의견이 갈리면서, 인민행동당이 분열된 것이다. 결국 림 친 시옹과 지지자들은 인민행동당을 떠나 사회주의전선을 창당했고, 말라야 연방 가입도 국민 투표에 부쳐지게 됐다.

같은 해 2월 ‘싱가포르 기자연합’(Singapore National Union of Journalists)의 창립 사무총장을 지냈던 마하데바는 “인민행동당이 유권자들에게 가입에 찬성할 것을 부추긴다”며 강력히 항의했다. 그는 싱가포르 기자연합이 정당정치를 한다는 주장에 반박하기 위해 “노조가 유권자의 선택을 부정하는 비민주적인 행동에 반대할 뿐”이라고 설명했지만, 리콴유는 이마저도 마하데바가 림 친 시옹의 편을 들어주는 당파적 행위라고 단정지어 버렸다.

사회주의전선은 유권자들에게 차라리 무효표라도 던져야 한다고 외쳤으나, 인민행동당은 무효표를 찬성표로 간주하도록 법률까지 개정했다. 1963년 9월 1일, 연방 가입 찬성표가 약 70%의 득표율을 기록했고, 싱가포르는 리콴유 총리의 생일인 9월 16일에 말라야 연방에 가입했다. 마하데바는 이에 따른 후폭풍으로 무거운 대가를 치러야 했다. 1963년 2월 2일, 좌익운동 소탕 작전으로 인해 그와 림 친 시옹을 비롯한 사회주의전선 동료 100여명이 체포된 것이다. 소탕 작전은 ‘콜드스토어(Operation Coldstore)라 불렸는데, 영국, 싱가포르, 말레이시아 정부가 싱가포르의 안보에 위협이 될 만한 모든 조직을 재기불능 상태로 만들고자 감행한 것이었다. 이들은 ‘공안조례 보존법’(Preservation of Public Security Ordinance, 현재는 Internal Security Act)에 의해 제대로 된 재판도 받지 못했다.

마하데바는 정녕 공산주의를 지지했을까?

31세의 젊은 사회운동가 마하데바는 모든 경력이 사라질 위기에 처했다. 스트레이츠 타임스는 그가 돌아오길 간절히 바랐음에도, 싱가포르 당국은 이를 허락치 않았다. 대중으로부터 잊혀진 그는 1968년 10월 29일 마침내 석방됐다. 이후 TV에 출연해 과거 ‘공산주의를 지지하는’ 활동에 참여했다고 고백했다. 스트레이츠 타임스는 이에 대해 “전직 기자이자 노동운동가였던 마하데바가 공산주의를 지지했다고 고백한 뒤 풀려났다”고 보도했다.

하지만 마하데바가 깊이 간직하고 있던 정치적 신념을 포기했는가 묻는다면, 나는 결코 아니었을 것이라고 답할 것이다. 마하데바가 별세한 뒤 공개된 회고록은 그가 처했던 곤경을 조망한다.

“그는 언론인으로서 서구 열강과 소련의 계속된 갈등 속에서 중립을 지키려는 반둥*을 지지했다. 림 친 시옹과 사회주의전선이 옹호하던 반둥은 싱가포르의 순조로운 독립을 위해 영국과 협력하던 리 총리의 실용주의와 완전히 상반된다.”

*역주: 반둥은 반제국주의의 기치 아래 아시아 및 아프리카의 29개국이 민족 독립, 인종 평등, 세계 평화, 주권 존중, 우호 협력 등을 내세운 평화 10원칙을 결의한 국제회의다.

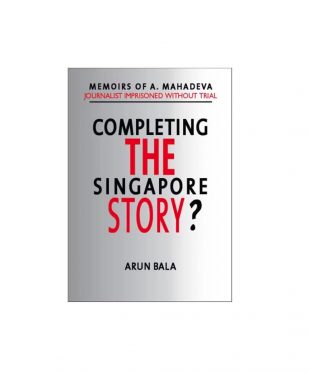

마하데바는 2005년 74세의 나이로 세상을 떠났지만, 후학인 아룬 발라 박사는 회고록을 통해 마하데바가 언론인이자 노동조합원으로서 공산주의자가 아닌 민주사회주의를 지지했다고 밝혔다. 올해 출간된 마하데바의 회고록 ‘Completing the Singapore Story?:Memoirs of A. Mahadeva ?Journalist Imprisoned Without Trial’은 언론의 독립성을 탄압한 리콴유를 고발했다. 이 책은 1998년 출판된 리콴유의 자서전 제목(The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew)을 풍자한 것으로 화제를 모은 바 있다.

위와 같은 사료들은 한때 싱가포르 총리가 될 뻔 했던 림 친 시옹의 정적 리콴유에 의해 압수돼 오랜 세월 수면 아래 머물렀고, 마하데바와 동료들이 겪었던 일련의 사건들은 싱가포르 언론에 어두운 그림자를 드리웠다. 번역 김동연 아시아엔 미주통신원

Run-Ins with Lee Kuan Yew Cut Short Young Activist’s Career

By Ivan Lim

On Sept. 27, 1957, a bright 26-year-old activist, Arun Mahadeva, or Maha for short, was invited to meet Lee Kuan Yew, 34, a United Kingdom-trained lawyer and up-and-coming politician who was soon to become Singapore’s Prime Minister.

At the meeting in Lee’s law office, the secretary general of the People’s Action Party offered the soon-to-graduate youngster an important job. This was to head a research unit, and the PAP was planning to set up Lee’s coming battle with left-wing rivals for trade union supremacy.

Not only that, the solicitous Lee also held up the prospect of fielding the activist in the general election in 1959.

But first Lee wanted Maha to indicate whether he would side with the PAP in the event of a split with his nemesis Lim Chin Siong, 24, a powerful union leader, who was later to head the competing Barisan Sosialis(BS).

The party’s democratic socialism ideology was similar to the PAP’s, but for its pro-labour orientation.

Maha, who knew Lim and his party’s platform, could not accede to Lee, saying he would keep an open mind; his stand would depend on the issues and how the contending parties resolved them.

Lee pressed Maha for a clear-cut answer but the latter replied it depended on the issues at stake and how the contending parties resolved them.

The meeting broke up with Maha having no job and getting into Lee’s list of opponents.

According to a new book on events that followed, Maha as a journalist and unionist was treated by Lee as a foe as the PAP, and the Barisan Sosialis fought it out in the early 1960s to gain power from the departing British authorities.

Titled Completing the Singapore Story?:Memoirs of A. Mahadeva ?Journalist Imprisoned Without Trial — shed light on Lee’s scant tolerance for independent political journalism, as seen in the way he dealt with the newsman. (The book is the latest in a series of writings offering a counter-narrative to The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew, published in 1998.)

In 1957, upon his graduation from the University of Malaya(a merger of King Edward VII College of Medicine and Raffles College set up by the British in Singapore), Maha joined the Singapore Tiger Standard and was quickly thrust into the hurly burly of the fast-changing politics of the day.

Then, as a reporter in The Straits Times, he had occasional run-ins with Prime Minister Lee, which left him wary of the politician.

In turn, their encounters and exchanges led Lee to view Maha, a partisan journalist aligned with Lim Chin Siong and his left wing cause.

As recounted in the memoirs, a dramatic exchange took place in 1959 during a general elections rally outside the Nanyang Shoe Factory in Bukit Timah.

On spotting Maha there, the PAP leader shouted out: “What story are you writing about? You don’t even name the person who received money from the CIA to help defeating the PAP.’’

He was referring to one Chew Swee Kee, whose identity had not yet been disclosed publicly.

Maha retorted that he was doing his duty as a reporter, writing about what he had learned through his investigations.

If Lee was prepared to name names, then, as a professional, Maha would report it. But Lee apparently found it politically inconvenient to do so.

And Maha would not go against his journalistic principles to help the PAP, sympathetic though he was, at that point, to the party’s democratic socialist platform.

While an undergraduate, he had joined the University of Malaya Socialist Club and embraced the democratic socialist cause espoused by the local elites fired up by nationalist feelings through post-War Asia, and taking up the charge to oust British in Singapore.

Among the activists he befriended were Sandra Woodhull, S.T. Bani and Dominic Puthucheary, who later headed trade unions involved in mobilising workers in the anti-colonial struggle.

Maha was circulation manager for the Socialist Club’s organization, the Fajar, which figured in a high-profile sedition case in 1954 brought against it by the colonial government for its editorial, “ Aggression in Asia.”

Maha also got to know closely Jamit Singh, the fire-brand chief of the left-wing Singapore Harbour Board Staff Association, and an early supporter of Lee Kuan Yew, who was elected in the port constituency of Tanjong Pagar.

Maha had done a study of the salary structure of Asian port workers for his final-year university thesis ? which could explain Lee’s earlier offer to Maha of a labour research post.

Through these contacts, Maha was to get to know union leader Lim Chin Siong, who was calling the shots in the anti-colonial movement of largely Chinese-educated rank-and-file in the private sector. Lim was regarded as the man who would be Prime Minister of an independent Singapore.

Meanwhile, a group of ‘returned students’ with lawyer Lee Kuan Yew, economist Goh Keng Swee and scientist Toh Chin Chye as its core, and agitating for de-colonisation in the Malayan Forum in London, began to tap into the Chinese mass movement.

Lee and Lim joined hands in forming the PAP to contest the British-sanctioned elections leading to self-government. Maha threw himself into the electioneering campaigns that saw the PAP triumph over the pro-establishment conservative Progressive Party. Lee became Prime Minister of a self-governing Singapore in March 1959.

But in 1961 there was a split in the PAP leadership over terms for joining the proposed Federation of Malaysia endorsed by the British to protect their interest in South-East Asia. Lim Chin Siong’s faction left to form the Barisan Socialis. The issue of merger with the federation of Malaya was put up for a national referendum.

Maha, who had become the founder secretary general of the Singapore National Union of Journalists (SNUJ) on February 12th, 1961, protested against the PAP’s merger proposals that asked voters to tick three boxes all in favour of the merger but without any provision for a say against it.

To rebut charges that SNUJ was playing party politics, Maha said the union was merely objecting to the undemocratic feature of the Bill in denying the voters the right to choose.

However, Lee saw it as a politically partisan act by Maha in siding with Lim Chin Siong, who also opposed the PAP formulated Bill.

In a tactical move, the Barisan Socialis urged voters to reject the bill by casting blank ballots, but the PAP quickly amended the law to count blank ballots as “yes” votes for merger. On September 1st, 1963, the ballot was cast and up to 70 per cent voted “yes” for the merger. Singapore joined the Federation of Malaysia on September 16th, the birthday of Lee Kuan Yew.

Whether he foresaw the coming storm or not, Maha was soon to pay a heavy price for exercising his right to comment and come out with criticisms.

On February 2nd, 1963, he was nabbed during a security sweep that targeted over 100 left-wing activists such as Lim Chin Siong and his Barisan Sosialis comrades.

They were detained without trial under the Preservation of Public Security Ordinance (now Internal Security Act).The sweep, codenamed Operation Coldstore by the Internal Security Council, was launched by the British, Singapore and Malaya authorities to cripple the activities of the communist united front organisations that purportedly posed a threat to Singapore’s internal security.

Maha’s incarceration was to cut short the 31-year-old activist’s media and union career to which he would not be able to return. The Singapore authorities saw to it that he would not be allowed to work as a journalist again even when the Straits Times was willing to take him back.

On October 29th, 1968, the forgotten detainee was freed after appearing on TV and reading out a Special Branch-scripted confession of his past ‘pro-communist” activities.

The Straits Times reported: “Former journalist and left-wing trade unionist Arunasalam Mahadeva was released from political detention today, after a public disavowal of his pro-communist activities six years ago.”

But did he recant his deeply-held political beliefs? No. The posthumous biography A. Mahadeva ?sheds new light on Maha’s quandary.

“As a journalist, he was more in tune with the so-called Bandung stance of staying neutral in the on-going conflict between the Western powers and the Soviet Union. This position, favoured by Lim Chin Siong and his party, was at variance with the pragmatism of Lee and his group of working with the British to achieve smooth transition to independence for Singapore.”

Mahadeva passed away in 2005 at age 74. His posthumous biography by his scholar- brother, Dr Arun Bala, itself a labour of love, vindicated Maha as an independent-minded principled journalist and trade unionist who hewed to the democratic socialist, non-communist, path.

It is a pitfall of journalism that his writings were seized upon by Lee Kuan Yew as politically aligned with the charismatic Lim Chin Siong, who could have been the Prime Minister of Singapore.